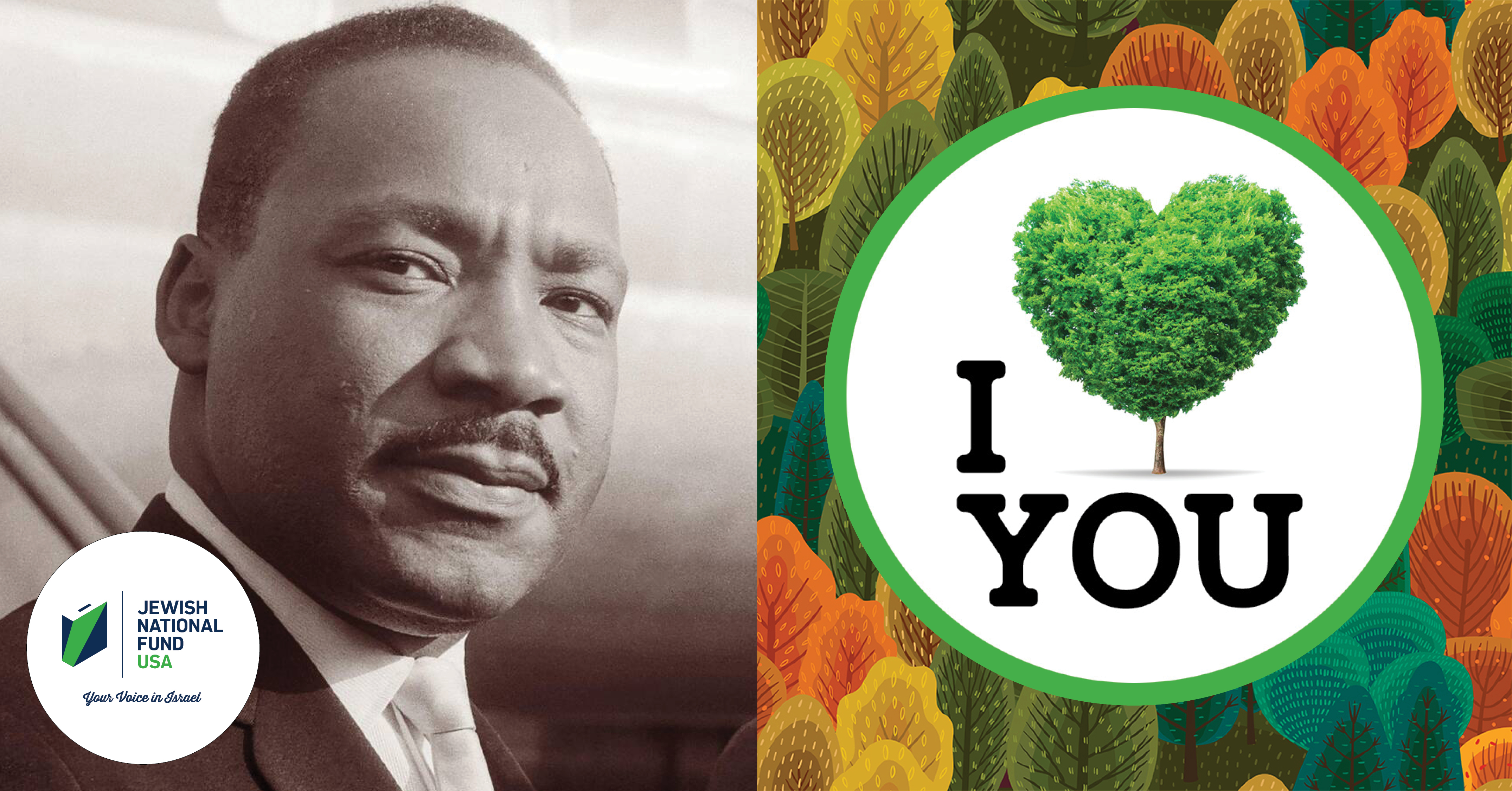

With MLK Day and Tu BiShvat falling on the same day this year, we remember the seeds of justice MLK planted and his legacy as an ardent supporter of the land and people of Israel and Jewish people everywhere.

Seeds of Justice Planted by MLK

Each year, millions of Americans celebrate the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his tireless fight for civil rights. However, in addition to his monumental legacy advocating for the rights of black Americans, he leaves behind a lesser-known legacy: one of Israel advocacy and fighting anti-Semitism. This year, with Martin Luther King Jr. Day and Tu BiShvat on the same day, it's perhaps fitting that we acknowledge the seeds of justice MLK planted all those decades ago as we metaphorically and physically recommit ourselves to renewed growth and making Earth a better place.

A Firm Commitment to Zionism and Combating Anti-Semitism

In 1968, a mere two weeks before his assassination, Dr. King said in a speech to the Rabbinical Assembly: "Peace for Israel means security, and we must stand with all our might to protect its right to exist…I see Israel as one of the great outposts of democracy in the world, and a marvelous example of what can be done, how desert land can be transformed into an oasis of brotherhood and democracy. Peace for Israel means security and that security must be a reality."

The Bond Between Black and Jewish Communities

Famously, King marched on Selma with Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel by his side, and the two remained friends until King’s death. In fact, 10 days before he was assassinated, King even spoke at an event celebrating Rabbi Heschel that was attended by over 1,000 rabbis. When Heschel spoke at King's funeral, he said, "Martin Luther King is a voice, a vision, and a way. I call upon every Jew to harken to his voice, to share his vision, to follow in his way."

MLK’s Values and Their Alignment with Jewish National Fund-USA

This year, with Martin Luther King Day on the same day as Tu Bishvat -- Jewish National Fund-USA’s unofficial "High Holiday" -- we are once again reminded of how intertwined Dr. King's values are with Jewish values, and by extension JNF-USA's. The responsibility of making the world a better place. The importance of believing in something greater than yourself. The significance of making the wonders of the world more accessible to all.

The Shared Responsibility to Make the World a Better Place

Renewing Our Commitment to Justice and Growth

You can continue the legacy of Martin Luther King and plant a tree in his honor at jnf.org/trees.

The Jewish National Fund-USA (JNF-USA) is a cornerstone of Israel’s development efforts, committed to creating a better future for the nation. Through comprehensive initiatives in environmental sustainability, community development, and education, JNF_USA has significantly contributed to the modernization and growth of Israel. By opting to donate to Israel via Jewish National Fund-USA, you support essential projects that drive progress and uplift communities across the country.